In the wake of U.S. elections, emotions often run high — especially when it comes to how political outcomes might affect financial markets. Financial Planning magazine asked 320 advisors “how will the US election outcome influence your retirement plan?” A staggering 90% anticipated a negative impact on their clients’ portfolios. This survey was from 2016, and neither the 2016 nor 2020 elections brought the lasting economic downturn that many anticipated. While some are anxiously bracing for an economic collapse and some are overly optimistic about the future after this most recent election, emotional responses on either end of the spectrum can lead to poor investment choices. Here are three key considerations to help you avoid making impulsive financial decisions based on political outcomes.

- Put things in perspective

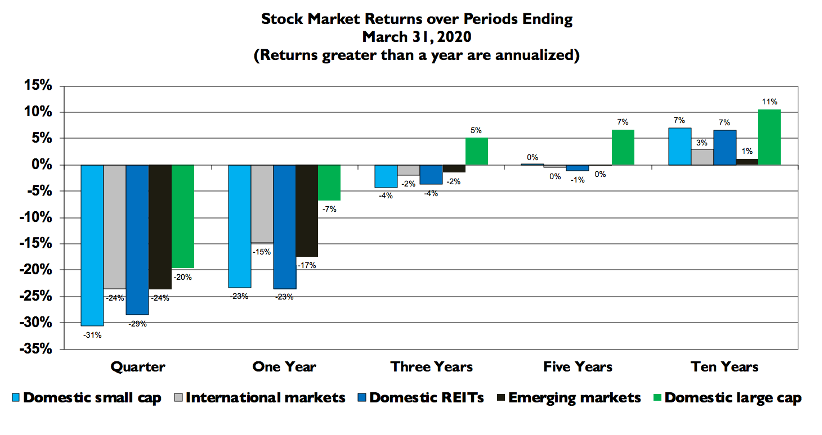

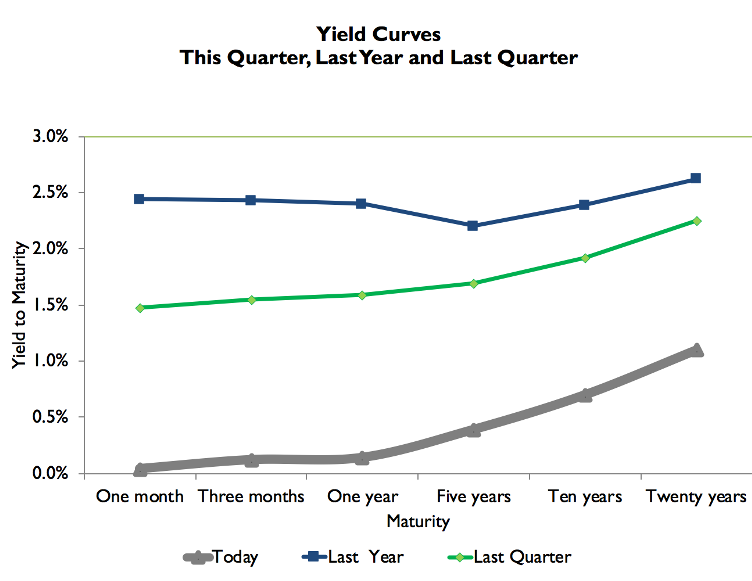

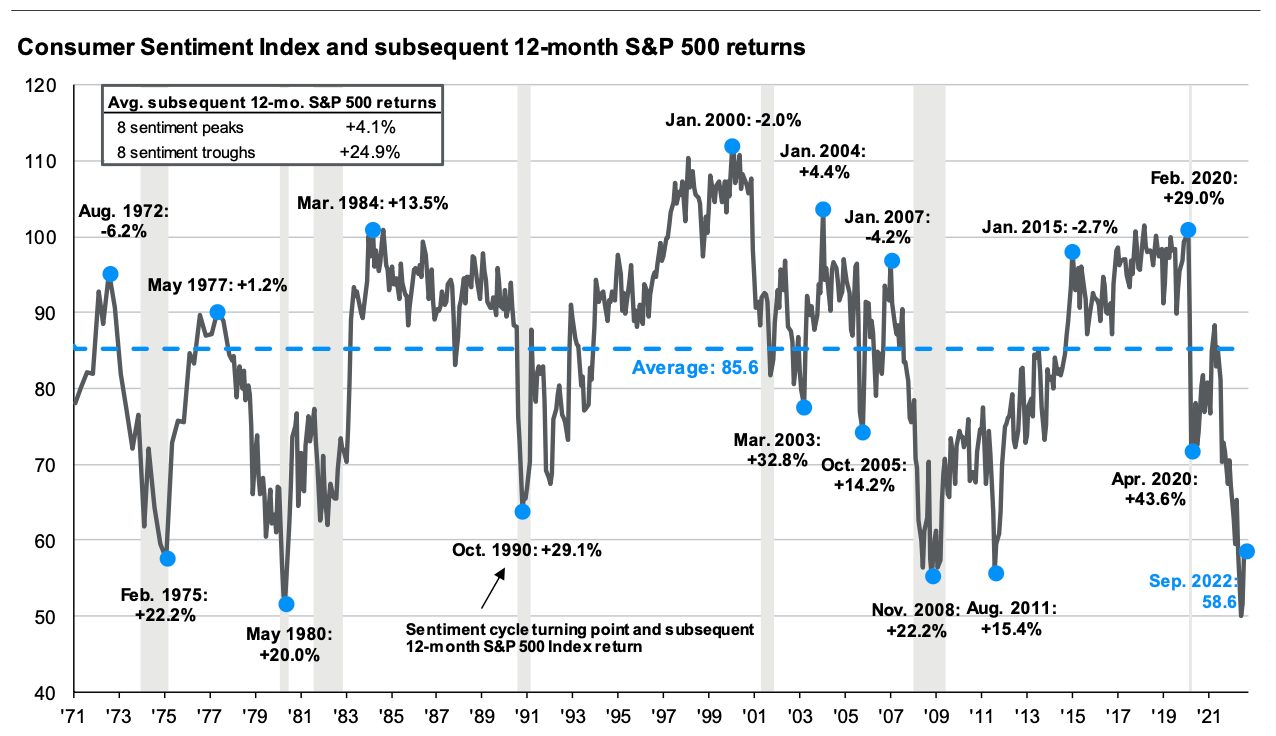

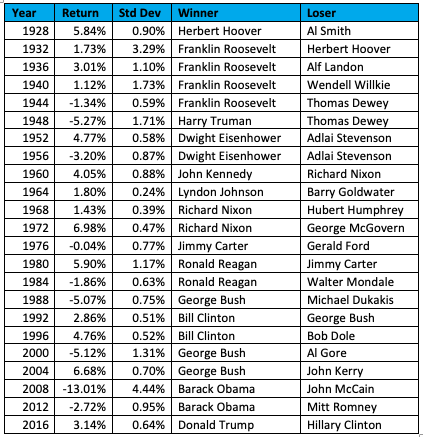

History shows that while the markets may react to major geopolitical events, these reactions are typically short-lived. A 2019 study from BlackRock highlighted that the market’s response to unexpected geopolitical shocks has historically been modest and brief. For investors, the key is not to focus on the current political climate but to look ahead—well beyond the next four years. While a president’s economic policies may cause temporary downturns, the long-term trend for the stock market has consistently been upward. Looking back at 20 presidential elections between 1944 and 2020, the S&P 500 posted positive returns in 16 of them, with a median gain of 5.6% in the 10 months leading up to those elections. This ties back to an article I had written prior to the election – that the market performs similarly whether it is a Democrat or Republican in office. This data suggests that, despite the political noise, the market is more influenced by economic fundamentals and corporate profitability than by who is in the Oval Office. Overall, you are betting on the market and that your long-term discipline wins over time, and data shows this strategy pays off.

- Manage Emotions

Emotional decisions can derail your investment strategy and significantly impact your long-term returns. Any adjustments to your portfolio should reflect your personal financial goals and circumstances, not the political noise surrounding an election. History has shown that missing just a handful of the market’s best days can drastically reduce your gains. According to a recent Wells Fargo report, over the past 30 years, if an S&P 500 investor missed the index’s 10 best days, their returns would have been 35% lower than a buy-and-hold strategy. Miss the top 20 days, and that number nearly doubles to a 60% loss in returns. It’s natural to feel uneasy during uncertain times, but it’s important to remember that emotional reactions are often a costly way to navigate the markets. After all, while certain events may seem overwhelming, they often have little lasting impact on the broader economy, which is driven by factors like the evolving business cycle, interest rates, and corporate profitability—forces far bigger than individual political outcomes. A simple tip to reduce emotional stress could be to turn off news alerts. Constant exposure to the headlines can amplify anxiety, so limiting intake may prove beneficial.

- Stick to the Plan

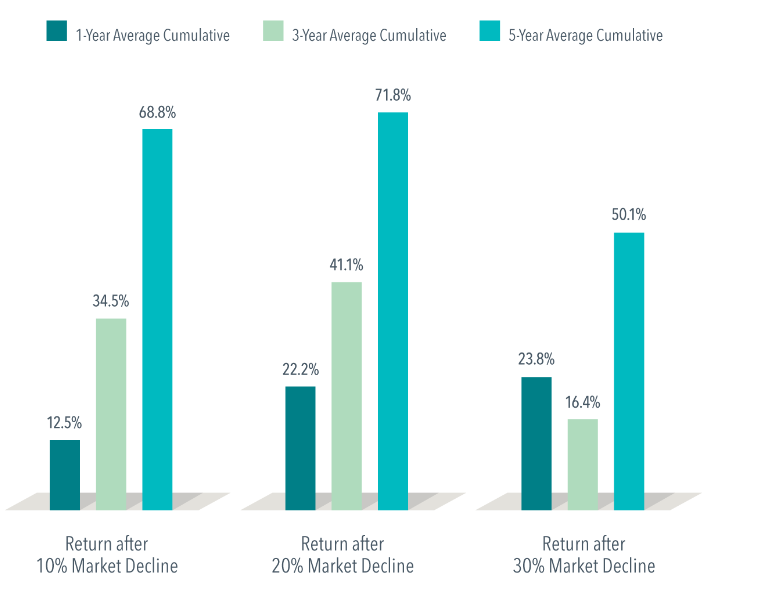

At Rockbridge, we believe the key to managing today’s geopolitical risks and uncertainties is not all that different from how we approach any other period of market volatility: with a well-diversified strategic asset allocation that aligns with your risk tolerance and long-term objectives. Our advice remains simple: stick to the plan. As a Rockbridge client, we implement a portfolio that accounts for your ability to withstand market downturns and ensures you have enough liquidity to maintain your lifestyle during uncertain times. Data consistently shows that sticking to your long-term strategy—rather than trying to time the market based on political events—leads to better outcomes over time. At Rockbridge, we encourage you to stay disciplined, avoid reacting to short-term political noise, and trust in the strategic consistency of your portfolio.

If you are still nervous, it’s important to ask yourself two key questions: how much of a market decline can you tolerate, and how much cash do you need readily available? If you don’t know the answer yourself, we encourage you to reach out to your Rockbridge advisor who can help ensure you are in a good position. Diversification remains the foundation of investing in a world that’s always shifting, giving portfolios the resilience to navigate all types of market storms. Challenges will inevitably arise, and geopolitical turmoil is just one of many factors that can trigger market turbulence. However, history has shown that staying invested in a well-diversified portfolio aligned with your long-term goals has helped investors weather numerous crises, wars, pandemics, and recessions. Rockbridge believes this approach will continue to serve investors well, no matter what the future holds.

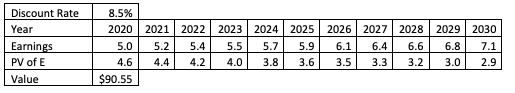

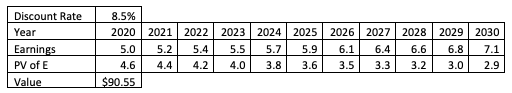

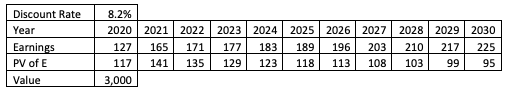

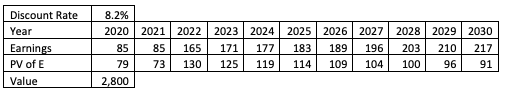

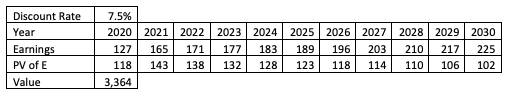

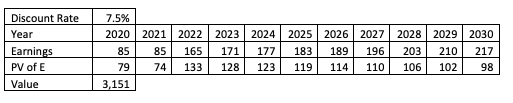

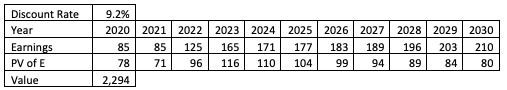

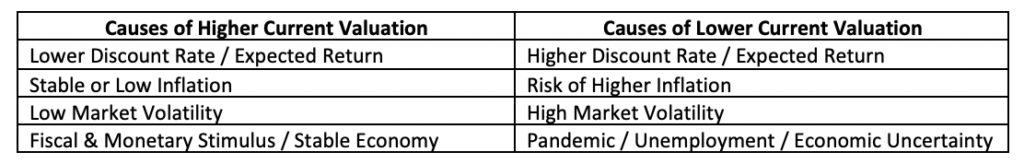

In the appendix of this article we run through several scenarios adjusting corporate earnings and discount rates to assess their impact on S&P 500 fair value. Some interesting observations:

In the appendix of this article we run through several scenarios adjusting corporate earnings and discount rates to assess their impact on S&P 500 fair value. Some interesting observations: