There’s been a lot of talk about recessions lately: Whether one is near, far, or perhaps already here. Whether we can or should try to avoid it. What it even means to be in a recession, and how it’s related to current market turmoil.

To put market and recessionary concerns in perspective, it might help to describe six ways a recession resembles a bad mood. There are some intriguing similarities!

1. There Is No Precise Definition.

We all know what a bad mood feels like. But there is no clear definition for a nebulous mix of real and perceived setbacks, and how they’re going to affect us.

Likewise, there is no single signal to tell us exactly when a recession is underway or when it’s over. Instead, recessions can trigger, and/or be triggered by a number of conditions connected in various fashions and to varying degrees. These usually include a declining Gross Domestic Product (GDP), along with rising unemployment, sinking consumer confidence, gloomy retail forecasts, disappointing corporate balance sheets, a bond yield curve inversion, stock market declines, and similar combinations of objective and subjective events.

In the U.S., the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) defines a recession as follows (emphasis ours):

“A recession is a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts for more than a few months.”

Rather vague, isn’t it? That’s intentionally done. Similarly, the World Bank Group has stated, “Despite the interest in global recessions, the term does not have a widely accepted definition.”

2. You Usually Can’t Spot One Except in Hindsight.

How do you know when you’re in a bad mood? Often, you don’t, until you’re looking back at it.

Recessions are similar. Since a widespread downturn must linger for a while before it even qualifies as a recession, the NBER only declares one after it’s underway. For example, in July 2020, the NBER announced we’d been in a recession for two months between February–April 2020. This was triggered, of course, by the abrupt arrival of the global pandemic. It was the shortest U.S. recession to date, and already over by the time we officially acknowledged it.

3. Sometimes, We Get Stuck for a While.

Hopefully, your bad moods come and go, resulting in more good times than bad. But sometimes, one misfortune feeds another until you feel gridlocked. It may take a while before improved conditions, a more upbeat attitude, or a blend of both help you move forward.

In similar fashion, recessions can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. As Nobel Laureate and Yale economist Robert Shiller describes, “The fear can lead to the actuality,” in which (for example) economic conditions might feed inflation, which inverts the bond yield curve, which signals a recession, which shakes corporate and consumer confidence, which leads to unfortunate reactions that further aggravate the challenges. And so on. When this occurs, a recession and its related financial fallout may last longer than the underlying economics alone might suggest.

4. They’re Inevitable.

It’s never fun to be in a bad mood, but we can all agree they’re part of life. It would be unhealthy, exhausting even, if we were endlessly giddy every minute of every day.

Similarly, nobody celebrates a recession. But it helps to recognize they aren’t aberrations; they are part of natural economic cycles. And while they may not be anyone’s favorite tool for the job, they can sometimes help rein in runaway spending, earning, and pricing for companies, consumers, and creditors alike.

For example, in our current climate, we may enter into a recession (or already be in one) as a byproduct of the interest rate increases, aimed at warding off rising inflation, amidst the backdrop of lingering COVID-19 supply side issues and global economic sanctions against Russia. If we can avoid a recession, all the better. But if it’s going to take a modest one to reduce inflation, it may be the preferred, if challenging choice at this time.

5. Experience Helps.

When we’re youngsters, we have little perspective to help us realize we won’t be miserable forever just because we’re unhappy in the moment. No wonder we give it our all, every time. As we mature, we learn to temper our moods, and/or seek support if we do get stuck in a rut.

The same can be said about recessions, and similar challenges. It’s been more than a decade since the Great Recession; and more than 40 years since the U.S. last experienced steep inflation. As such, many investors have had little first-hand experience managing such turbulent times.

It may help to acknowledge we’ve been here before. While commenting on the most recent two-month recession in 2020, “A Wealth of Common Sense” blogger Ben Carlson lists nearly three dozen distinct U.S. recessions dating back to the 1850s, with an average length of 17 months. Some were considerably longer. We endured a series of years-long recessions during the era of the Civil War in the mid- to late-1800s. Then there was the Great Depression from 1929–1939.

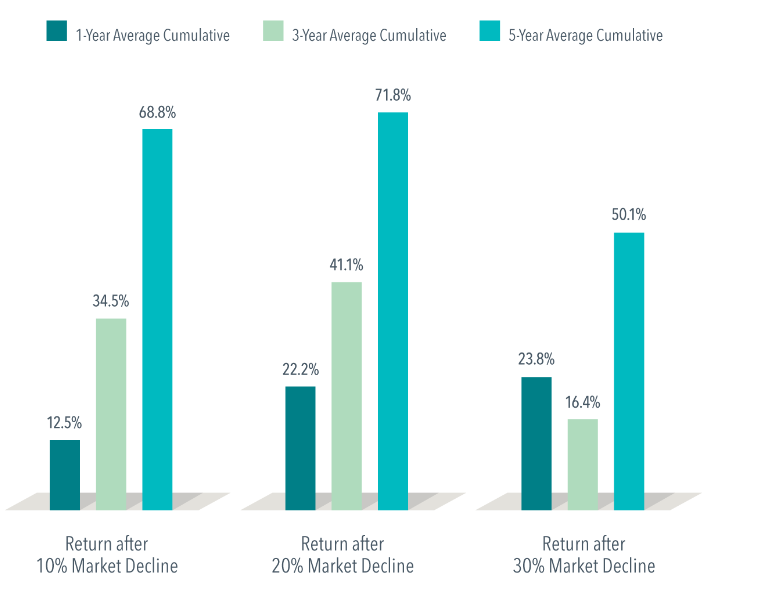

It also helps to remember: Every recession has eventually ended, with economies and markets thriving thereafter. As Dimensional Fund Advisors shows us, one-, three- and five-year average cumulative returns after significant U.S. stock market declines dating back to July 1926 have all been positive, rewarding investors who placed their faith in future expected returns. Since markets are ultimately driven by the underlying growth in global commerce, we can expect similar aggregate performance moving forward in domestic and international markets alike.

Consider these words of wisdom from one of the most experienced investors of all, Warren Buffett, in his 2012 Berkshire Hathaway shareholders letter (emphasis ours):

“Periodic setbacks will occur, yes, but investors and [business] managers are in a game that is heavily stacked in their favor. … Since the basic game is so favorable, Charlie [Munger] and I believe it’s a terrible mistake to try to dance in and out of it based upon the turn of tarot cards, the predictions of ‘experts,’ or the ebb and flow of business activity. The risks of being out of the game are huge compared to the risks of being in it.”

6. You Can’t Change Others, But You Can Change Yourself.

When you’re in a funk, it doesn’t matter whether it’s due to one or many unfortunate events, or “just because.” There’s ultimately only one person who can change your mood: yourself.

The same is true for your response to recessions, bear markets, and other external events standing between you and your financial wellbeing. Life is filled with causes and effects over which we have no control, especially with respect to our investments. And yet, there are many small, but mighty acts we can take to contribute to the positive outcomes we wish to see in our homes, our nation, and the world. We can manage our household budgets. We can show up for work (or perhaps volunteer in retirement). We can be loving family members, engaged citizens, and generous donors to the causes we hold dear.

And, we can invest wisely. This means taking charge of your personal wealth by focusing on the drivers you can control, and ignoring the greater forces you can’t. For example:

• We can’t avoid recessions. But we can channel our inner Warren Buffett to look past today’s risks, and retain an appropriate amount of market exposure in pursuit of our long-term financial goals.

• We can’t avoid bear markets. But we can avoid generating unnecessary losses by panicking and selling low in the middle of one.

• We can’t avoid inflation. But we can establish a thoughtful budget to track our income and spending, with a plan in place for making adjustments as warranted.

Last and hardly least: It’s very hard to change the world. But you can always change yourself. Sometimes all it takes is a shift in sentiment to seize your next best move. As always, we’re available to assist with that in any way we can. How can we be of service to you and your family? Don’t hesitate to be in touch.