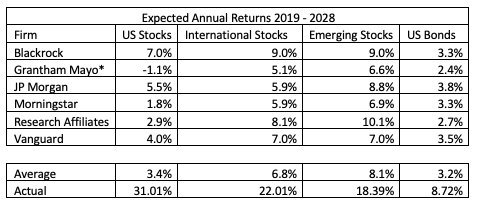

Each year large Wall Street firms post their expected returns for the next decade. A year ago, we saw the following forecasts:

* Denotes a seven-year forecast

The biggest thing that stands out here is the poor performance expected by U.S. Equities. Despite 93 years of annualized returns in excess of 9.5%, the best research minds in the country were only forecasting an average of 3.4% for the ensuing 10 years. It is also interesting how much better they expect returns from non-U.S. stocks to be than from U.S. stocks.

Another thing to note is how far off last year’s realized returns are from the forecasted returns. For U.S. Stocks, an annualized 3.4% for a decade works out to a gain of 39.7%. If that were to be true, we got more than three-quarters of that gain just in the last year.

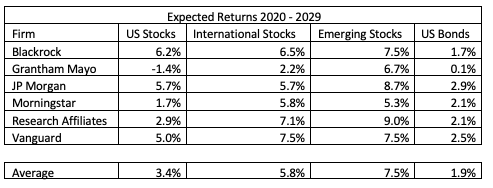

The following table shows the same companies and their expected returns for the next decade.

Relative to last year, it is interesting to see that U.S. Equities still have the same expected return, despite their great run in 2019. Expected returns from non-U.S. Stocks came down some but are still quite a bit higher than U.S. Stocks. One takeaway is that the U.S. economy and expected future earnings beat expectations last year by a greater margin than they did overseas. Still, overseas prospects are apparently brighter. Another interesting item is the expected return of U.S. bonds. The prediction fell from 3.2% to 1.9%, which is a function of interest rates falling. Currently, the U.S. Aggregate bond market is yielding 2.2%. To realize a 1.9% return off of a 2.2% yield means the underlying value of the bonds must be decreasing (interest rates are rising). The implied increase interest rates over the next decade would have to be towards the end of the decade and at least 0.50% for this to hold true.

We can think of a few takeaways from this information. First, despite the poor performance of international equities over the last decade, we believe it would be a mistake to reduce international equity allocation at this time. Second, markets are very hard to predict and years or even a decade can be short when it comes to markets and economic cycles.

A foolish investor last year would have seen an expected 3.4% return from U.S. Stocks and have been tempted to look elsewhere. If they had done that, they would have missed out on a 31% gain. We are again reminded that the most prudent thing is to stay diversified and stay invested while ensuring you are making all the correct decisions when it comes to saving and financial planning.