More to Savings Bonds Than Just Interest:

Savings bonds are perhaps the best interest-paying savings these days, with the banks paying little or no interest on savings and checking accounts and interest on CDs at an all-time low. Savings bonds are typically long-term savings. Several tax clients cashed in their long-term savings bonds in 2013, incurring lots of ordinary income and related tax liability.

One advantage, besides the better interest rates, is that the interest is not subject to state taxes. However, all of the interest is subject to federal taxes, and federal tax rates are generally much more than state tax rates. One big disadvantage is that there is no “step-up” in basis for the one who inherits them. The “basis” of most other financial assets (stocks, bonds, property), when inherited, is the value at the date of death when calculating gain or loss at the time of sale, and the gain is considered to be “long-term.” Not so with savings bonds.

Given this fact, it might be advantageous to set up an annual schedule to cash in savings bonds, possibly paying less tax and avoiding the inclusion of this income in the Social Security income calculation. Most are unaware of this tax treatment, and surprised at the tax on this inherited asset. This is the kind of thing that should be discussed with your investment advisor when planning on cash flow from your investments or savings.

Do You Know What is in Your Account?:

One tax client had sales of securities to report from two brokers. The number of stocks sold for 2013 was 159 individual stocks. She had no idea why there were so many sales and what stocks were actually in her accounts. One would wonder why an account would have that many individual securities, and we are only talking about those stocks that were sold in 2013. I didn’t see what was bought because it was not relevant to the tax preparation!

It is not critical that investors know exactly what each investment is, but they must be able to get an explanation from the investment advisor if it is desired. When this many stocks are bought or sold, I immediately begin to wonder if the transactions are made to benefit the client, or the salesperson. And good luck doing the capital gains portion of a tax return with this many short- and long-term transactions!!

Take Advantage of Your Investment Advisor:

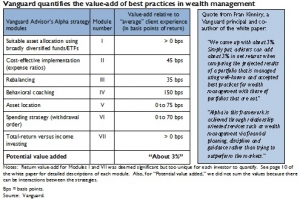

One client explained that he wanted to file “married filing separately” although he was married the entire year and is still living with his wife. They were not separated. I explained that there was a considerable difference in the tax rates for this status, but he told me his wife had already filed this way because she had created a trust and thought they no longer qualified as “married filing jointly”. Their tax liability filing separately was $10,739. The tax liability for filing jointly was $8,967. The creation of a trust has no bearing on the decision on filing status, and a mistake like this can be costly. The investment advisor, along with the attorney, should be part of any decision to move assets to a trust so these kinds of issues can be discussed. Rockbridge has a “value proposition” stating “Helping clients make sound financial decisions through a comprehensive client experience.” We hope clients will include us and use our expertise in their financial decisions.

Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs):

An annual occurrence seems to be a tale of the investment advisor or custodian who doesn’t follow up with the client who should have made a required distribution from his/her IRA account. In this case, enough was taken from another IRA account to satisfy the minimum, but it was just accidental that it worked out. One advisor just failed to contact the client to assure the proper distribution be made. At Rockbridge we pay special attention to assure compliance for our clients.

At the end of a year and at “tax time” it is an ideal time to think about your investments and review your financial situation. Take advantage of your investment advisor and their expertise in financial areas such as income taxes, retirement planning, investing, Social Security benefits, cash flow needs, and estate planning. Call us at Rockbridge to discuss your accounts or to become a valued client.