Professor Teresa Ghilarducci has an opinion piece in the NY Times this week lambasting our evolving approach to retirement. She has some good points.

Tara Siegel Bernard writes in the NY Times, “Most investors don’t realize that when they walk into a bank or brokerage firm branch, the representatives there are essentially free to emblazon their business cards with whatever titles they please — financial consultants, advisers, wealth managers, to name a few. But if you’re looking for someone who is qualified to give smart advice about all aspects of your financial life while keeping costs down, you may not be in the right place.”

She goes on to say, “Still, the biggest danger right now, experts say, goes back to the fact that most consumers don’t know who they are dealing with when they sit down with a broker.” She quotes Arthur Laby, a professor at Rutgers School of Law-Camden, and a former assistant general counsel at the S.E.C. “The greatest risk the average investor runs is the risk of being misled into thinking that the broker is acting in the best interest of the client, as opposed to acting in the firm’s interest.”

To see the full article go to: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/07/your-money/beware-of-fancy-financial-adviser-titles.html?_r=1&src=me&ref=your-money

The global equity markets continue to experience disappointing returns. In discussions with clients, my advice is a reminder that the research shows that developing a strategic asset allocation plan and staying the course through rebalancing is the prudent course of action.

The European sovereign debt crisis is in its third year and continues to create great uncertainty in global financial markets. Investors globally are expressing concern about the impact of the crisis on economic growth rates and the financial system. Understandably, this is an anxious time for investors.

Europe’s inability to deal conclusively with its problems is discouraging. It is obvious that the issues facing Europe will not be resolved in the short run. But exiting European investments entirely seems like an overreaction. In fact, European equity price/earnings ratio, a common means of valuation, indicates that European equities are reasonably priced. It is certainly better to invest when valuations are low, and one should never make investment decisions based on today’s headlines.

A deep European recession would likely have a moderate impact on the U.S. economy. Europe accounts for 15% of total U.S. exports or about 2% of U.S. GDP. European markets represent 14% of total revenue of the S&P 500 companies. The U.S. economy should prove resilient enough to weather the most likely bad scenarios – e.g., weaker countries such as Greece exit the euro.

Economic problems exist in Spain, France, Italy, Portugal and Greece. Greece has been generating most of the headlines, but it is a small country by market capitalization and therefore makes up a very small portion of portfolio holdings within the global equity funds that Rockbridge utilizes.

Of course, global equity funds also have sizable holdings in non-European markets, both developed and emerging. These markets have had mixed recent results.

Exposure to international equities, which often behave differently than domestic equities, are a way to provide the diversification that tempers a portfolio’s volatility. Basing investment decisions on headlines, fear, or speculation is always counterproductive. Being calm and disciplined with our asset allocation strategies is the better approach. If you have concerns on your allocation to global equities, talk to us.

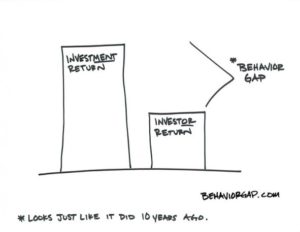

Dalbar, an independent communications and research firm, has done countless studies trying to quantify the impact of investor behavior on real-life returns. Their studies focus on the difference between investors’ actual returns in stock funds to the average return of the funds themselves. Basically, they are comparing the return the investor gets to the return the investments get.

The results are eye-opening! In 2011 Dalbar found that the average equity fund investor underperformed the broad U.S. index return (S&P 500) by 7.85%. This difference in return comes from investors making classic behavioral mistakes time and time again. In my eyes, an investor’s biggest hurdles to reaching financial success are their own ego and emotions, and these are probably the two hardest things to overcome!

The results are eye-opening! In 2011 Dalbar found that the average equity fund investor underperformed the broad U.S. index return (S&P 500) by 7.85%. This difference in return comes from investors making classic behavioral mistakes time and time again. In my eyes, an investor’s biggest hurdles to reaching financial success are their own ego and emotions, and these are probably the two hardest things to overcome!

The numerous market gyrations of the past decade have challenged even the most disciplined investors and caused many people to run for safety. These tend to be the most challenging times for us as advisors, because it involves avoiding what feels like a good decision at the time and helping you come up with what might be the more logical one. Basically, helping YOU, not your EMOTIONS, run your retirement account.

The two vertical lines on the graph at right (at March ’09 and September ’11) represent the times in which we fielded the most client calls here at Rockbridge. The markets were down drastically and, rightfully so, investors were nervous about what to do with their money. The common theme we heard was, “Should we pull the money out now and wait for the market to gain some stability?” Much to their discomfort at the time we did the contrary and held course. The blue line shows the outcome of staying invested for the full decade, while the red line shows how moving out of the market and into “cash” at the wrong times can affect your long-term performance. In this particular scenario, poor timing in the market cost the investor over $70,000 during the decade.

The two vertical lines on the graph at right (at March ’09 and September ’11) represent the times in which we fielded the most client calls here at Rockbridge. The markets were down drastically and, rightfully so, investors were nervous about what to do with their money. The common theme we heard was, “Should we pull the money out now and wait for the market to gain some stability?” Much to their discomfort at the time we did the contrary and held course. The blue line shows the outcome of staying invested for the full decade, while the red line shows how moving out of the market and into “cash” at the wrong times can affect your long-term performance. In this particular scenario, poor timing in the market cost the investor over $70,000 during the decade.

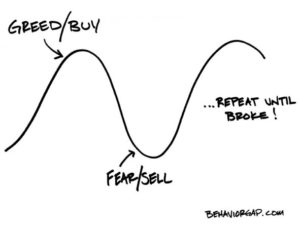

The picture below also illustrates what not to do in investing. If you buy when the market is up, or sell when the market is down (out of fear or your emotions), you will do nothing but hurt yourself financially. So maybe we need to look at this drawing upside down and remember what Warren Buffet continually preaches: Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful!

Buffet continually preaches: Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful!

Remember that successful investing is about “controlling the controllable and ignoring the rest.” We can’t control the direction of the financial markets, but we can avoid making costly mistakes by attempting to do so. The smartest people I know are the ones who understand that they don’t know everything and put policies in place to protect their portfolios from their own emotional behavior. When it comes to financial success, slow and steady does WIN the race!

ONE: Focus on the near term. A recent headline reads, Anxious financial advisers scale back summer vacations. “Still haunted by the 2008 financial crisis, many financial advisers are scaling back their summer vacations or giving up on them entirely. Many are afraid to be out of the office in case this is the third straight summer in which markets are hit with severe volatility.” Reuters (21 Jun.)

Staying home from vacation to do what? These statements seem to imply that a smart, clever advisor will know what action to take when news breaks. Buy, sell, move everything to cash until markets stabilize?

It is unfortunate that investors can only determine market stability after the market reacts to the hope or possibility of stability. It sounds so appealing to stay out of volatile markets and invest only when we can expect stable, positive returns, but by the time stability appears, prices have risen, and it’s too late. We expect successful business managers to take action when presented with new information, but an emotional reaction to new information can be very dangerous for an investor, leading them to buy high and sell low.

TWO: Touting what would have worked in the last crisis. Hedging, or insuring against volatility is also appealing – who wouldn’t want the return without the risk? Keep in mind that insurance companies make a profit by accepting a transfer of risk. The same is true in financial markets. Just like dental insurance premiums are sometimes less than what you collect in annual benefits (you win!), portfolio insurance sometimes pays off, but on average the insurance company makes money, and on average portfolio insurance reduces your expected return. Remember, expected return is a function of how much risk you are willing to accept. Therefore any strategy that reduces your risk to zero will also reduce your expected return to zero – or less because of the insurance premium.

THREE: It’s different this time. No really, it’s different. Much industry attention is now focused on the current trend of adding alternative investments like hedge funds and private equity to a portfolio because their results are not correlated with stocks. Diversification is the only free lunch in investing. Blending together a mix of different asset classes with different risk and return characteristics can produce a portfolio with a better balance of risk and return than any of the individual asset classes. However, it can be argued that calling hedge funds a separate asset class is like calling lottery tickets a separate asset class, because their results are not correlated with the stock market! Hiring a hedge fund manager to buy some stocks and sell others short is likely to produce uncorrelated results but not necessarily improve portfolio results.

FOUR: Holding up winning bets as if they resulted from skill rather than luck. The popular press, as well as the financial industry media, loves to idolize winners. They talk about trading strategies, hedging strategies, managing volatility, etc. It seems ironic to me that almost everyone acknowledges the futility of day trading, that popular pastime of the late 1990’s when people thought they could make a living buying and selling stocks in a rapidly rising market. Yet we are still seduced by the current crop of strategies that are based on the same underlying notion – that someone can outsmart markets by predicting the future when the outcome is unknowable.

Some questions to help you avoid the hype surrounding the next great idea put forth by the financial media:

- Does it make sense as a long-term strategy?

- Is it based on an understanding of how markets work, or does success hinge on someone predicting unknowable outcomes?

- Is it really a different kind of asset or just a familiar asset class in an expensive wrapper that cleverly alters short-term results (indexed annuities and buffered investment contracts come to mind)?

- Will a successful result come from skill, or luck, and is there any way to judge skill in advance?

These are important questions for long-term investors who want to avoid the pitfalls of emotional response to market volatility.

Equity markets had a rough second quarter. For the period ending June 30, 2012 the S&P 500 index (large stocks) was down 2.8%, the Russell 2000 index (small stocks) was down 3.5%, and the MSCI EAFE index (international stocks) was down 6.9%. The international index might have seen a double-digit decline were it not for some good news on the European debt crisis and a big rally on the last trading day of the quarter.

At the end of the first quarter I noted that, “the European debt crisis seems far from solved, and yet just the absence of bad news has had a surprisingly positive effect on global equity markets.” Bad news returned in the second quarter, and the results reflect it. Of course the discouraging new information was not limited to Europe as the Chinese economy showed signs of slowing down, and the U.S. recovery continues to struggle. Nonetheless, returns for the year to date remain in positive territory, even for the international markets.

Portfolio returns were also buoyed by the strength of fixed income returns. The broad bond index that we track was up 2.6% and some long-term government bond funds were up 12%. The yield on 30-year Treasury bonds fell from 3.35% to 2.76% during the quarter, causing the jump in value, but reflecting the market’s expectation that low interest rates will persist for many years. For anyone who thinks rates MUST go up from these levels, it is instructive to consider Japan. Ten-year government bonds in Japan have been around or below 2% since 1998 and now provide a yield of just 0.85% (U.S. 10-year debt was yielding 1.67% at the end of the quarter).

2012 is showing once again that stock market returns can only be enjoyed if we are willing to accept risk and volatility. We can also observe the benefit of diversification and the way bonds reduce volatility in a stock portfolio.